Monday

15th November

2004-

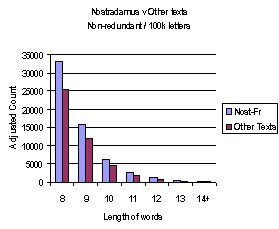

Both the emotional and rational minds are astounded

by the result. The expectation of each was that after the adjustments

described earlier there would be nothing of significance in a comparison

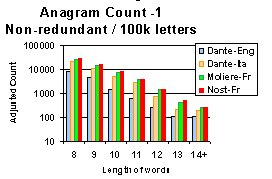

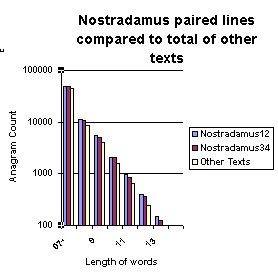

of the Nostradamus' text with the others. Below is the chart of the

results of the analysis.

The graph displays words

of length greater than 7. The word base was filtered by me for

words below 6 as these smaller words become so easy to find that

any deliberate anagrammatisation would be hard to see. The

analysis below 8 words is therefore discarded in the presentation

of all charts.

The results show that there is a clear and consistent pattern

in all groupings that place Nostradamus' text well above the other

texts.

The right hand, emotional side of the brain is pleased but apprehensive at this

result for although it seems this is a clear victory it knows the

left-hand side too well, this result will be pursued to try and find its

logical flaw.

And the emotional side is

also disappointed for it aches for the issue to

be resolved and a negative result would have allowed this quest to end. Nothing is proven

by this result, it just continues the pattern whereby

Nostradamus text

continues to intrigue and puzzle me.

Already the computers are running once more, running logical tests to

try and resolve what it means when an analysis of a French text using

English words leads to this surprising

result.

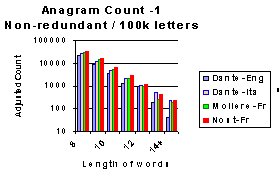

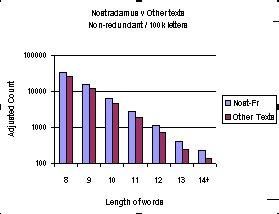

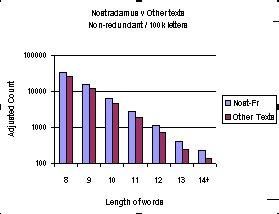

This process of understanding begins with the graph below, which uses a

logarithmic scale to display the result. This shows much more clearly that

as the length of words increases there is a distinct increase in the ratio

of Nostradamus count compared to that of the Other texts.

A normal scale uses equal

intervals on the vertical axis to show the same gap in count. In

the previous graph (above) each label on the vertical scale is evenly spaced

and is 500 counts greater than the one below it. The normal graph is excellent for

small vertical ranges.

A normal scale uses equal

intervals on the vertical axis to show the same gap in count. In

the previous graph (above) each label on the vertical scale is evenly spaced

and is 500 counts greater than the one below it. The normal graph is excellent for

small vertical ranges.

A logarithmic scale shows proportions much better when the

graph covers a large range. In the graph alongside each label on

the vertical axis is evenly spaced but is 10 times greater than

the one below it.

This graph suggests that a straight line could be drawn across

the tops of each Series. Each line has a distinctive slope and

they come together at some point to the left of the graph

It would not be surprising to see such a result if there was deliberate

coding for it is less masked where randomly generated anagrams are less

frequent (i.e. longer words).

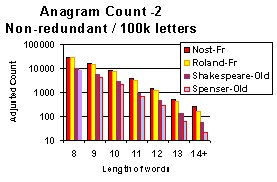

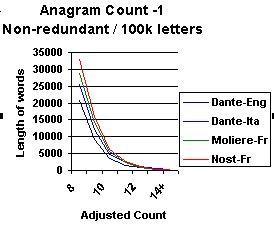

Potential for Code in the Other Texts

The reason for choosing several texts in

different languages was to try and quantify the extent of random anagram

generation. Dante in modern English was expected to be particularly

significant in this regard for it is nigh impossible for it to contain

coding.

Several of the texts were from a period in time where coding

in text was very fashionable. It has been implied that Shakespeare's work

may hide code in the forms of anagrams but the selection of sonnets makes

this selection unlikely to be coded (for the nature of the word is

paramount in sonnets). The same can be said for Moliere who was writing a play that

needed to be attuned to the ear, not the mind.

Saga's are different

for in telling a story, elegance is less important, So Dante's Italian and

Roland's Chansong hold greater potential for concealing code

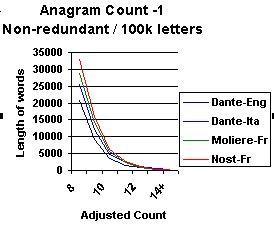

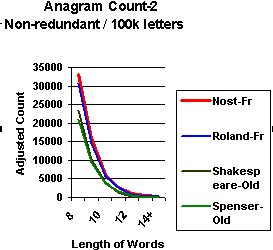

The results

for each of the different sources is shown alongside, this time using a line

rather than column graph.

The results

for each of the different sources is shown alongside, this time using a line

rather than column graph.

Nostradamus text remains above each of the other texts

throughout the range (Except at 13+ stage where Dante-Italian

exceeds Nostradamus).

Dante's English version falls into the pattern that could be

expected for an uncoded work. It has the least number of anagrams.

Shakespeares sonnets also fit to the expectation but Moliere does

not. It lies closer to the Nostradamus text than anticipated. So

is it coded or is there an error or a structural

explanation?

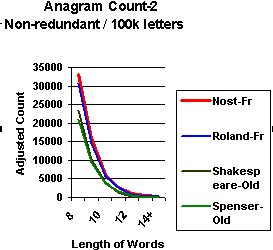

Roland's Chansong and Dante's Italian version show the signs

that could imply coding- they lie beneath Nostradamus but above

the one's expected not to show any signs of code.

The two genuine

English sources, Shakespeare and Spenser

show a slightly greater count than the Dante version but less than

their French counterparts. This result is indeed intriguing and

could be a reflection of coding but it might indicate a flaw in

the methodology.

The two genuine

English sources, Shakespeare and Spenser

show a slightly greater count than the Dante version but less than

their French counterparts. This result is indeed intriguing and

could be a reflection of coding but it might indicate a flaw in

the methodology.

They imply a need for some simple tests.

The sources have unequal numbers of letters in them and it is important

to test whether my equalisation factor distorts the result. The nature of

the data is such that a simple test can be provided.

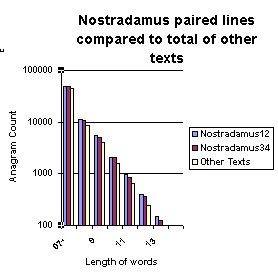

The sum of the Other

Source letters is very nearly equal to half the letters In Nostradamus. By

using 2 line pairings of Nostradamus' four- line-quatrains as a basis for

comparison

it can be shown the results still hold.

The nature of the

paired line graph alongside has additional confirmation to a trend

apparent in the earlier charts. It implies that the best chance of

determining the existence of code occurs in the analysis of longer

words found in each text.

The nature of the

paired line graph alongside has additional confirmation to a trend

apparent in the earlier charts. It implies that the best chance of

determining the existence of code occurs in the analysis of longer

words found in each text.

The evidence, although it doesn't prove there is coding, does

have a direct bearing on the search, for it indicates the things

which need to be tested.

The research at this point sheds little light on whether this

coding was in English and certainly it tells us nothing about the

purpose of any code that might be contained in any text. These are

aspects that can perhaps be resolved once some of the issues

regarding this part of the search are more fully answered.

Amongst the

significant questions that are raised by

these results is the reason why

the texts written in foreign

languages show a tendency to imply code when examined with an

English word base. Even if they are in code it would seem unlikely

they are coded in their own language. Simple logic suggests that

testing

with an English base should not reveal a coding pattern in another

language. However simple logic often leads to wrong conclusions (as in the

case of "Which one of

a lead, wooden and glass ball of same

size will fall fastest when dropped?-They all fall at the same rate).

The simple logic suggesting English (or another foreign base) would not

work is undermined by the connections of profiles in different languages.

In this series of analyses I am not actually looking for

English words in other language texts, I am looking for anagrams

of English words.

In preparing for this analysis I have drawn upon the Moby reference source to construct both a French

and an Italian word base. I have then examined them using my anagram

profile functions and MS Access query tools. These foreign word bases are not as big as the English word base but

they show that between 16% and 20% of the anagram profiles in the smaller

bases are common to each other and the English word base.

| 1stSource |

No. of Unique profiles in list 1 |

2nd Source |

No. of Unique profiles in list 2 |

Common profiles |

| English |

310,000 |

French |

120,000 |

24,955 (20%) |

| French |

120,000 |

Italian |

52,000 |

8002 of (16%) |

| Italian |

52,000 |

English |

310,000 |

9251 (18%) |

This is a high percentage and if to this is added the very significant

number that have very-similar profile then we will always get a large

number of anagrams no matter what language is used,. However, the expectation would be that the variance

between those with and without coding should increase when analysed with the

appropriate language base (that in which the code is written).

It is evident from this that I should at least run a full test using the

French Word base to see if the results hold and to see what is revealed.

This research has shown that a huge number of anagrams of varying

lengths occur by chance. (The number of occurrences is certainly much larger than

I expected.)

I consequently believe that the finding of anagrammatic structures in

any text is extremely likely and that the ability to find chance sequences

that suggest a meaningful relationship are also high.

From this we can conclude that:

- the finding of a

pattern in a very small and restricted set can't and shouldn't imply it

was deliberately implanted.

- the superabundance of anagrams to be found in all texts means it cannot be argued that chance alone supports

the import of any single message.

- it renders

meaningless those anagrams formed by letter substitutions- such practices

are no more than

a license to fantasise.

- Gematria and Temurah methods of reading texts would appear to have the

same order of credibility as tea-leaf reading.

Yet we know code does exist in many texts and in order to assess it

we need a more rigid understanding of what is abnormal and what can occur

by chance.

In order to go beyond this issue of probability and create a firmer

base, an understanding of the

findings in the earliest part of the research are essential.

In order to pursue this I have created two different functions to randomise the order in

the search lines. This means they contain the same letters but the

syllabic structures are destroyed. This has then been used to analyse 1 in

every 9 of the search lines in each Word base. Exact correlations

can therefore be created for each line that is examined

in its

original and randomised state.

Tuesday 16th November

2004- The French analyses

are complete and I have the

computers running once more. They are testing randomisation when the word

base is in English.

Since there are a different number of words in the English and French

data bases it needs to be highlighted that my comparison for different

languages is of form

rather than quantity. It is difficult to know at this stage what impact

trebling the word base has, it is highly unlikely to produce 3 times as

many anagrams (per 100k letters) and

is unlikely to have a definable

factor. However in the two bases I have used this factor for non-redunadant

anagrams seems to be

between 1.40 (unique word-forms only) and 1.55 (non-unique forms included-

e.g repetitions such as

rat, art, tar).

The English word base I have used is so large because it includes a vast

number of technical names and terms from a range of sciences and human

endeavours. These are not part of the French word-base although many (such

as chemical names) would be identical in each.

The reason for running the French word base is that a pattern seems

to have emerged from the English analysis - it shows a distinct

difference in the sources that is consistent over the full range of

word-lengths.

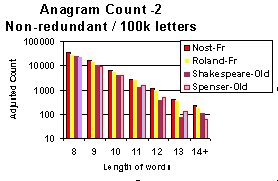

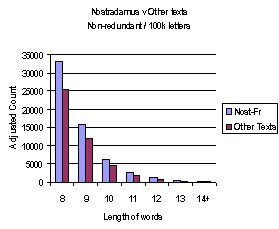

The graphs below comparing the new French analysis to the earlier

English one use a slightly different format to that used earlier- (logarithmic

columns where each interval is ten times the one below it). They are

divided into two groups (Count 1 and Count 2) and the results for the

English and French word bases are shown alongside each other.

Significantly, when looking at the new results using a French

lexicon base, there is no change

in the order of the sources and there is no change in the consistency of

the result over the range of word-lengths.

One reason for running the program using the French data was to test

whether the low result for the English sources was due to something

inbuilt into my program that prejudiced the result against the host

language. These graphs show that this is not the case- the English sources

are still poorly performed while all the French sources are very highly

performed. Dante's English version performs

worst

in both

languages. This English version of Dante was tested as a form of control (highly

improbable that it is in code) and its placement provides no reason to

dismiss the theory that these anagrams are revealing the potential for

hidden code. And

Shakespeare's Sonnets support this view- they give a better comparative

performance under English analysis than in French. We can therefore

conclude that on the sample tested my methodology produces consistent

outcomes across various languages.

There are still important issues to be resolved because at this point

we have observed a difference but not offered any reason as

to why the English and French sources differ in

the counts found in both word bases. However English is built on a

historical basis and offers many more alternative word forms than French.

These alternatives are derived from a whole host of invader-based sources

and therefore English is likely to perform well across many

languages.

In the next section of this paper I look at the classes of words in

Nostradamus text in order to discover whether there are imbalances or

themes that support the idea of coding. In the rst of this paper I look at

the impact of randomising letters for those more interested in coding

methodology.

Sunday

21st November

2004- I have spent the last few days trying to understand

and then present the results of my random-letter analyses.

My hope was to produce a formula for the measurement of coding in any

text. Although I cannot provide a totally definitive measure I believe the

following provides a fair comparison basis Adjusted Anagram Count= Anagram

Count x Word-Base-Size-Factor (1.55 for French, 1.0 for English).

I believe that it is essential in any measurement for any data to be

assessed in the following ways.

- Analysis using a word base in the same language as to that in which

the text is written.

- Analysis of the text using a different language word base

- Analysis of a text known not to be coded.

- At least one analysis of the randomised lettering of the lines of

text.

The first two allow a measure to be made of the randomised and

non-randomised generation of anagrams.

My results from randomising lettering.

The purpose of my randomised lettering test was to establish a base

level for anagrams generated from a randomly ordered lettering set.

The first method I applied was to randomise the order of the lettering

in the line based on a random number generator. This caused a marked drop

in the count for every source. However, I realized this form of generator

might well preserve syllabic structures (just as random shuffling of cards

can preserve flushes etc.). In order to break these down I used a second

method.

The second method involved dividing the letters into four (1,5,9 etc,

2,6,10 and so on) then placing these groups one after the other. The

result of this was a further significant fall in the number of anagrams.

This analysis has an immediate import on the relevance of Nostradamus

text. The text I have used for the analysis is derived from Erika

Cheetham's "The Final Prophecies of Notradamus" -Warner Books

-1993. In her preface she says "Note to Reader: The French text of

the quatrains reproduces as closely as possible that of the original

edition of 1568 (Benoist Rigaud, Lyon).."

Now this text is most

peculiar, replacing u's with v's and v's with u's and using words and

using many spellings no one has been able to attribute to normal patterns.

e.g. The fourth line says "Fait psperer q n'est a croire vain."

It would be expected that on the basis of this oddity throughout the text

that Nostradamus

text should be below the other texts, not above them, when

any anagram count is taken. I can conclude on the basis of the

randomisation effect that the high count for Nostradamus' text is likely to be

understated.

There is also a significant pattern to be found when

looking at the results for same language Text and Word-base versus ones

that are different. This is much easier to interpret after a fair

allowance is made for the difference in Word-base size (I applied a factor

of 1.55). A

consistent fall applies when analysed

with a word-base in a language different from the source. This fall

persists even when the line of text is randomised. The result using my two

methods of randomisation lead to similar values and imply that there is a

1 in 6 decrease in count level whenever measuring English and French. This

is independent of the direction (i.e Enlish Text to French base, French

text to English word base). This has to be due to structural constraints

between the two languages and in particular in the frequencies of letter

usage.

Count of words

with more than 6 letters -Non-Redundant anagrams/100k letters

Text

in original order

|

Source |

Wordbase

Same-Lang |

Wordbase

Diff-Lang |

adjusted

Same-Lang |

adjusted

Diff-Lang |

ratio

S/D |

|

French

Sources |

93413 |

113388 |

144790 |

113388 |

1.28 |

|

Nost-Fr |

98188 |

123724 |

152191 |

123724 |

1.23 |

|

English

Sources |

79842 |

32155 |

79842 |

49840 |

1.60 |

Text randomised by 4

way split

|

Source |

Wordbase

Same-Lang |

Wordbase

Diff-Lang |

adjusted

Same-Lang |

adjusted

Diff-Lang |

ratio

S/D |

|

French

Sources |

42960 |

57246 |

66588 |

57246 |

1.16 |

|

Nost-Fr |

44451 |

61547 |

68899 |

61547 |

1.12 |

|

English

Sources |

42873 |

24135 |

42873 |

37409 |

1.15 |

Although there is a smaller difference in this ratio for the

Nostradamus' data it isn't enough to conclude that Nostradamus' text is

coded in any language other than French (if at all).

However, this

fall in count for language also implies that the count for Nostradamus'

text is understated. His text is known to include Provencal, Latin and a

variety of

language variations. At best there impact should be

neutral but in all probability they would mean the count given is

understated.

There is a distinct difference in the results for the

English sources and the French sources. Part of this arises because the

English base is less English than might be expected. It incorporates many

French words that are used in English. There are 13, 870 words that are

common to the French and English data bases.

When these words are

removed and each data base is showing its true language characteristics

there is still a bias against anagrams in the English sources. A

significant shift is however seen in the ratio's of same to different

anagram counts. Nostradamus' text falls further behind implying that it is

less pure in its use of the French Language.

|

Source |

Wordbase

Same-Lang |

Wordbase

Diff-Lang |

adjusted

Same-Lang |

adjusted

Diff-Lang |

ratio

S/D |

|

French

Sources |

78244 |

93666 |

125190 |

93666 |

1.33 |

|

Nost-Fr |

86165 |

109413 |

137864 |

109413 |

1.26 |

|

English

Sources |

79590 |

32611 |

79590 |

52178 |

1.52 |

The difference between the English and French counts may still include

a structural component but even so the results show that once more

Nostradamus' text is different to the other French texts. Once more

through its high anagram counts it consistently points to the possibility

of anagrammatic code.

At this point I would conclude that contrary to

expectations Nostradamus' text has withstood my analysis. It consistently

outperforms the other texts, across all

categories. Further the nature of

the text implies that this result is made more relevant because there are

valid reasons for believing the count to be understated.

These

conclusions imply that the analysis should be taken a stage further with

there still being a possibility that Nostradamus' text is not in French

and may be multilingual.

In this

part of the analysis I have looked solely at the statistical nature of the

anagrams, devoid of any relevance. The next step is to analyse the words

that have been uncovered and see if they hold some measurable

significance. The next stages will perform the following:

- Analyse the longer words into categories

- Determine whether the count for these categories deviate from

those within the word-base.

- Analyse whether there is any association between words in

specific locations.

|

NEXT STAGE OF ANALYSIS

Click here |

The results

for each of the different sources is shown alongside, this time using a line

rather than column graph.

The results

for each of the different sources is shown alongside, this time using a line

rather than column graph.

T

T